Wills and Family History

Documents of some 75,000 individuals who lived and died between the early 16th century and the mid-19th century are held in the probate collection of Durham diocese. These are the records of the many kinds of people - farmers, merchants, widows, clerks, lords, labourers - who lived in County Durham and Northumberland and who died either testate or intestate (without a will), and whose affairs then passed through the Durham church courts. The North East Inheritance project has photographed and catalogued these records in order to make them available online to historians and researchers around the world.

As a resource for genealogists wills are a crucial means of reconstructing family relationships and of tracing the transfer of property from generation to generation. Probate bonds, inventories and accounts, where they |

|

|

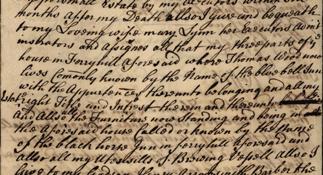

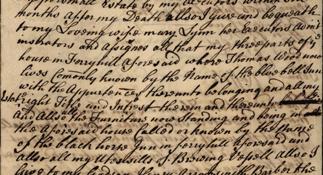

Will of Thomas Lynn, made on 4 December 1749. Lynn was the innkeeper of the Black Horse Inn

at Ferryhill, and part-owner of the Blue Bell Inn, also in Ferryhill. Every inn was a free house at this

time, and Lynn's bequest of his brewing equipment indicates he was serving home-brewed beer to

his customers. The will also supplies the names of seven living relatives and three witnesses.

Ref: DPRI/1/1752/L5/1-2. |

survive, can also play an important and perhaps less appreciated part in the story. When considered together, as the new catalogue conveniently allows, these records can supply a treasury of detail and allow our ancestors to speak directly to us at a significant moment in their lives.

Relationships

The first step for most family historians is to harvest the names from a will, and which can

number from zero to tens of dozens in any one document; these may be relatives or

friends, employees or business partners, debtors or creditors, and all manner of

relationships that grow up over a lifetime. |

|

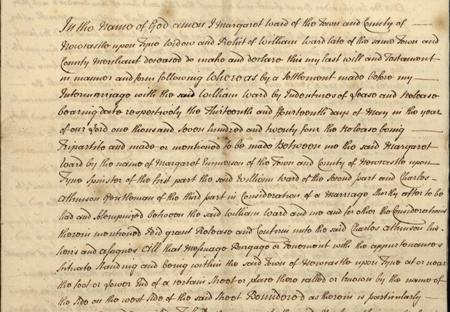

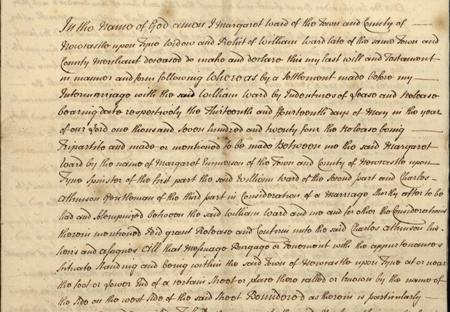

Sometimes marriage settlements can be recited in wills. In this case a widow of Newcastle named Margaret Ward (née Emmerson) exercises a right that was negotiated at her marriage eighteen years previously, that should she survive her husband she might raise £250 from a property in the Side that she had brought with her to the marriage, and which is to be paid upon her death to her son Charles Ward, clerk. The probate records of men are much more common than for women, and among women widows outnumber spinsters. Due to laws that prevailed until the Married Women's Property Act in 1882 married women had very limited property rights, and indeed could not make a will without their husband's consent, and which consent could still be revoked by a husband after his wife's death.

Ref: DPRI/1/1743/W7/1-2. |

Past Lives

| But there is much more that can be drawn from wills. Testators often describe where and perhaps in what style they wish to be buried, and the date of probate or administration can narrow down a date of death. The style of the statement of faith at the start of the will can be an indicator of religious conviction. Wills can also demonstrate the education and literacy of the writer. Sometimes narratives of long forgotten family events and misadventures can even be recovered. |

|

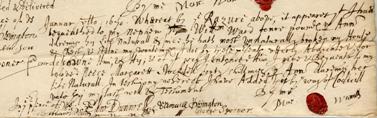

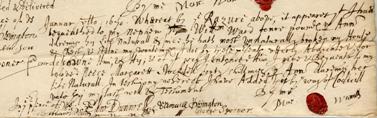

Codicil of Marmaduke Ward of Hurworth, gentleman, dated 31 January 1671. Three months earlier he had made his will in which he left a legacy of £4 a year for life to his nephew William Ward, but this bequest was then revoked because William 'hath most unnaturally broken my House & Chest, & stolne my writeinges'. The testator raged 'I doe by these presentes utterly Abdicate & forever disowne Him, & His' and angrily struck out the original bequest.

Ref: DPRI/1/1681/W3/1. |

Other Probate Records

Other probate records should not be neglected, particularly as they can supply

information for persons who made no will. Probate bonds can record the identity, status

and place of residence of the executor and administrator, and will also supply the names

of sureties who are often linked in some way with the family. Particularly after 1700, when

inventories become rare, bonds can also supply a rough total value of the personal

property of the deceased.

Probate inventories are wonderfully detailed lists of goods and chattels. They itemise the

daily objects, tools and stock of our ancestors' houses and working lives. |

|

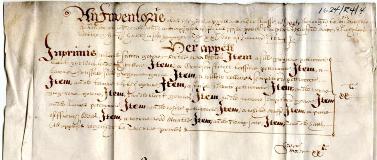

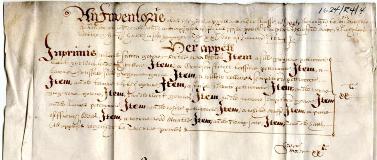

Extract from the probate inventory of Margerie Richardson of Durham, widow, appraised 20 January 1625. She lived in some style, and the list of her apparel includes a crimson stitched taffeta petticoat, a more practical 'willow collomed sempiternum [everlasting] petticoate', a white muff and a French bodice.

Ref: DPRI/1/1624/R4/4. |

As such they are very useful guides to the style in which people lived, to agricultural and trade practice, and to the tastes of consumers of the time. As these documents move from room to barn and from shop to field, they illustrate the life and work of a society and economy now long

past, and at a personal level can even re-clothe a testator before our eyes.

Probate records briefly illuminate and immediately make accessible to the researcher the

world and the outlook of our ancestors. Often living in the same landscape as ourselves,

and certainly with many of the same cares, these vital records offer an unrivalled

opportunity to family historians. Happy hunting!